In the 1st installment of this particular Blog topic, I randomly offered two 160 contest graphics

- one for the Stew Perry 160 contest and one the CQ 160 GiG) - to fill out the blog entry.

The impression might be assumed that I was slighting the ARRL-160 contest, when in fact,

I believe the ARRL 160 GiG was the 1st of all the exclusively 160-meter events: altho, like the

Stew Perry GiG it is a Cw only contest (fine by me). I believe the CQ-160 Ssb contest was/is

the first of its kind.

Because 160-meters is largely a nighttime band, I think an interesting addition to all these

events would be to double the QSO-points for contacts made before 18:00 your local time.

With computerized LCR (Log Checking Robot) software used by contest committees, it

should be relatively easy to determine what the time of day is in your particular time zone.

160 is the "localness" of communication possible

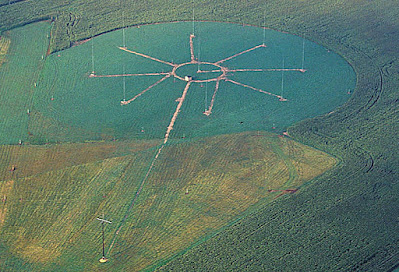

using antennas with [so-called] NVIS directional characteristics, yet with monster antennas like

the 3-square vertical array @WA6TQT's Radio Ranch (essentially 3 switchably-phased 128' broadcast towers), the world can be worked.

Of course, having access to 1.5kw amplifiers feeding those antennas makes a BiG difference.

Then again, some amazing 160-contest scores have been submitted by QRP stations.

Overall, jam-packed band conditions are encountered far less on 160 (than other HF bands) as fewer stations are comfortably 160-capable. Then again, many stations that ARE able to run 160, due to their NVIS-nature cannot be heard far away anyway; so overall, pileups on

160 are of a different nature than on the shorter wavelength bands.

One of the secrets to success on 160-meters is working the GREYLINE.

This phenomenon occurs every sunrise and sunset.

During Greyline periods, there is still proper atmospheric ionization on BOTH ends of the circuit, approximately 1 - 2 hours before/after sunrise/sunset. While other bands can experience greyline phenomenon (namely 80 & 40), on 160, w/o taking advantage of greyline propagation, working certain areas of the world is virtually impossible. Unlike the 40 - 10 meter bands, there is no propagation activity, requiring that we physically tune the bands and/or look for callsign spots to determine

when the band is open, and to where.

Then again, another approach is to utilize the RBN spotting network, call CQ and note how

many skimmer receivers can actually decode our signal. I've written things about the RBN.

[CLICK HERE] to read about it.

Being at opposite ends of the HF spectrum, 10 and 160 meters are unique challenges.

The challenge of 10-meters is largely a daytime phenomenon, while the challenge of the

160-meter band occurs largely at night.

What about YOU?

Do you ever find time to play around on 160-Meters.

What is your FAVorite frequency there?

.Jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment